The iconic great white shark, a top predator vital to marine ecosystems, is facing a dire future in the Mediterranean Sea, with new research revealing an alarming decline in its already fragile population. Scientists from a US university, working in close collaboration with the UK-based conservation charity Blue Marine Foundation, have published findings indicating that illegal fishing practices are a significant driver of this catastrophic trend. Their investigations have uncovered evidence of some of the most threatened species, including great white sharks, being openly sold in fish markets across North Africa, directly undermining international conservation efforts.

Great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) are among more than 20 shark species in the Mediterranean that benefit from robust protection under international law. This legal framework explicitly prohibits their capture, retention, sale, or trade. However, by meticulously monitoring fishing ports along the Mediterranean coastline of North Africa, researchers have made a startling discovery: at least 40 great white sharks have been killed and brought ashore in 2025 alone. This figure is particularly devastating for a population already teetering on the brink.

Beyond the researchers’ direct observations, the BBC has conducted its own investigation, independently verifying disturbing social media footage that depicts protected sharks being landed deceased at North African ports. One particularly harrowing video shows a colossal great white shark being laboriously hauled ashore from a fishing vessel in Algeria, its lifeless form a stark testament to the illegal trade. Another piece of footage, filmed in Tunisia, reveals the severed heads and fins of what appear to be short-finned mako sharks – another critically endangered and internationally protected species – being prepared for sale, highlighting the brazen nature of these illicit activities.

Last shark stronghold

Dr. Francesco Ferretti, a lead researcher from Virginia Tech, a prominent US university, articulated the gravity of the situation during an interview with the BBC News science team from a research vessel off the coast of Sicily in late 2025. He explained that many shark populations, with white sharks being a prime example, have experienced a dramatic and precipitous decline across the Mediterranean basin in recent decades. The region, unlike virtually any other stretch of ocean, endures relentless fishing pressure. "No other stretch of water is fished like the Mediterranean Sea," Dr. Ferretti emphasized, painting a grim picture of an ecosystem under siege. "The impact of industrial fishing has been intensifying… and it’s plausible that they will go extinct in the near future." This assessment underscores the urgency of the situation, given the great white’s slow reproductive rate and critical role as an apex predator in maintaining marine health.

The Mediterranean white shark population has been formally classified as "Critically Endangered" by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the global authority on the conservation status of species. This designation signifies that the species faces an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild.

In their latest and most ambitious attempt to locate and study these elusive predators, Dr. Ferretti and his dedicated team focused their efforts on the Strait of Sicily. This strategically important area, situated between the island of Sicily and the North African mainland, has been identified by scientists as a crucial "last stronghold" for several threatened shark species, including the great white. The primary objective of their mission was to achieve a groundbreaking feat: to successfully fit a satellite tracking tag onto a white shark, an action that has never been accomplished in the Mediterranean Sea, offering invaluable insights into their movements and behaviour.

To maximize their chances of encountering these rare giants, the researchers spared no expense or effort. They brought aboard more than three tonnes of fish bait – a massive shipping container brimming with frozen mackerel and tuna scraps. In addition, they deployed 500 litres of tuna oil, meticulously creating a vast "fat slick" designed to spread across the water’s surface, releasing an irresistible scent that sharks could detect from hundreds of metres away. Their methodology also included the deployment of baited hooks, the collection of seawater samples for environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis, and the use of sophisticated underwater cameras, all aimed at detecting any sign of the elusive sharks.

Despite two weeks of intensive effort, deploying vast quantities of bait, meticulously sampling the ocean, and continuously monitoring with advanced cameras, the researchers were met with profound disappointment. They did not manage to find any great white sharks to tag. Their efforts yielded only a fleeting, brief glimpse of a single blue shark captured on their submarine cameras, a stark indicator of the severe depletion of shark populations in the region.

"It’s disheartening," Dr. Ferretti confided, his voice reflecting the profound frustration and concern of the team. "It just shows how degraded this ecosystem is." The failure to locate even one great white shark to tag, despite such extensive preparations and targeting a known hotspot, painted a grim picture of the Mediterranean’s ecological health. The disappointment was compounded when, while the team was still actively searching for surviving sharks, they received distressing reports: a juvenile great white shark had been caught and killed in a North African fishery, a mere 20 nautical miles from their research vessel. It remains unclear whether this animal was an accidental bycatch or deliberately targeted. However, Dr. Ferretti and his team’s grim estimate of over 40 great white sharks caught along that coast in 2025 alone underscores the immense pressure on this critically endangered population. "This is a lot for a critically endangered population," he stressed, highlighting the unsustainable rate of loss.

Sharks for sale

The collaborative efforts between Dr. Ferretti’s research team, their colleagues in North Africa, and the BBC Forensics team have continued to monitor several fishing ports in the region. This extensive work provides undeniable evidence that protected sharks are routinely caught, landed, and openly offered for sale in countries such as Tunisia and Algeria. The social media footage independently verified by the BBC offers compelling visual proof. The video from Algeria, showing a great white being landed, shocked many, given the species’ protected status. Another clip from Tunisia depicted what appeared to be a large short-finned mako shark, its body dismembered, with heads and fins visible on a trolley, being prepared for market sale – a stark violation of international agreements.

The legal framework designed to protect these magnificent creatures is complex. Currently, 24 threatened species of sharks and rays, including iconic species like the mako, angel shark, thresher shark, and hammerhead shark, benefit from international legal protection. The European Union and 23 nations bordering the Mediterranean Sea are signatories to a critical agreement established by the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM). This agreement unequivocally states that these protected species cannot be "retained on board, transhipped, landed, transferred, stored, sold or displayed or offered for sale." Furthermore, the international accord mandates that "they must be released unharmed and alive [where] possible." However, a significant challenge lies in the fact that these rules do not explicitly tackle accidental bycatch with the same stringency, and the enforcement of these regulations varies considerably from one country to another, creating loopholes that are exploited by illegal fishers.

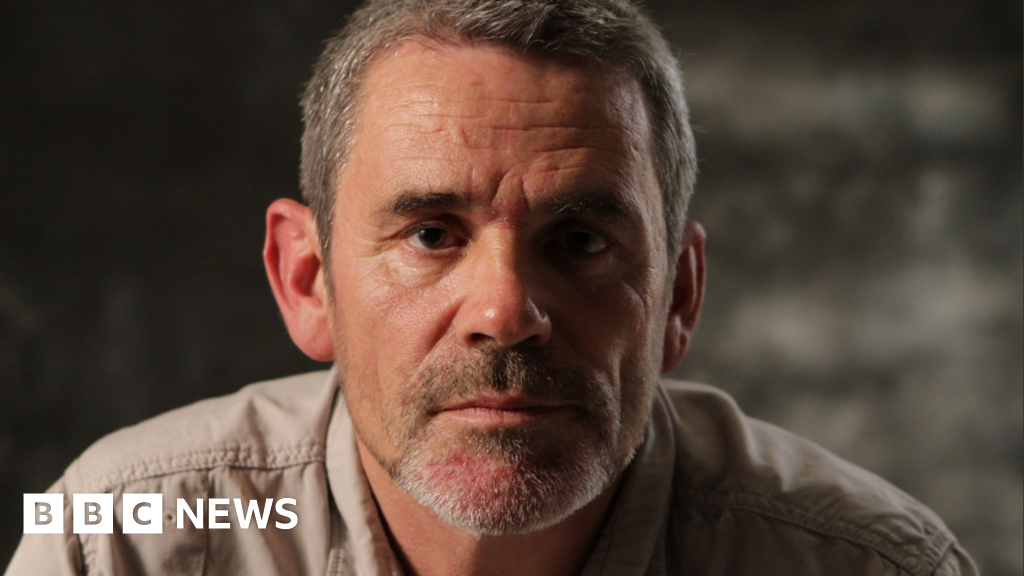

James Glancy from Blue Marine, a passionate conservationist involved in the project, recounted his own investigations in Tunisian fish markets in 2023, where he personally observed multiple white sharks openly for sale. Despite the disheartening nature of these discoveries, Glancy articulated a paradoxical element of hope. "It shows that there is wildlife left," he told BBC News. "And if we can preserve this, there is a chance of recovery." His sentiment suggests that while the situation is dire, the continued presence of even a small number of these animals means that concerted and effective conservation measures could still potentially reverse the trend towards extinction. The fact that they are being caught, tragically, confirms their continued existence, offering a sliver of hope for future recovery if action is taken swiftly and decisively.

What can be done?

Addressing the crisis requires a multifaceted approach that acknowledges the socio-economic realities faced by fishing communities. In poorer communities across North Africa, fishers who inadvertently or deliberately catch sharks often face an agonizing choice: to adhere to conservation laws and release a valuable catch, or to sell it to feed their families. Sara Almabruk, representing the Libyan Marine Biology Society, articulates this dilemma powerfully. She suggests that while many catches in North African waters might be accidental, the economic imperative is overwhelming. "Why would they throw sharks back into the sea when they need food for their children?" she questioned. Her perspective highlights the need for practical, community-focused solutions. "If you support them and train them in more sustainable fishing, they will not catch white sharks – or any sharks." This calls for investment in alternative livelihoods, education on sustainable fishing practices, and robust compensation schemes for fishers who release protected species.

James Glancy of Blue Marine echoed this sentiment, emphasizing the critical role of international collaboration. He asserted that if countries around the Mediterranean can unite and work together on comprehensive conservation strategies, "there is hope." This cooperation would entail not only harmonized enforcement of existing laws but also shared resources for monitoring, funding for sustainable alternatives, and widespread public awareness campaigns to shift consumer demand away from endangered species. However, Glancy delivered a stark warning that underscores the urgency of the situation: "But," he added, "we’ve got to act very quickly." The window of opportunity to save the Mediterranean great white shark is rapidly closing, and without immediate, coordinated action, these magnificent predators, vital to the health of our oceans, could vanish forever from these historic waters.