The villa’s location within a historical deer park is particularly crucial to its pristine condition. Unlike many Roman sites across Britain that have suffered degradation from centuries of ploughing or subsequent construction, this land has remained largely undisturbed. This unique circumstance means the villa’s remains, lying less than a metre below the surface, are expected to be remarkably well preserved, offering an archaeological treasure trove. The collaborative effort behind this monumental discovery involves experts from Swansea University, Neath Port Talbot Council, and Margam Abbey Church. They collectively believe the find offers "unparalleled information about Wales’ national story," promising to reshape our understanding of Roman life in the region.

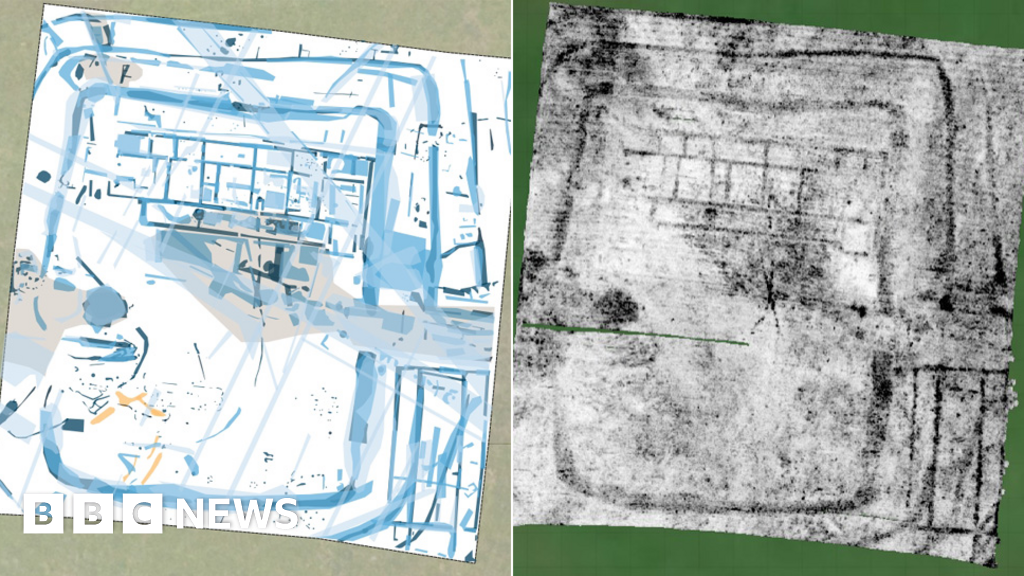

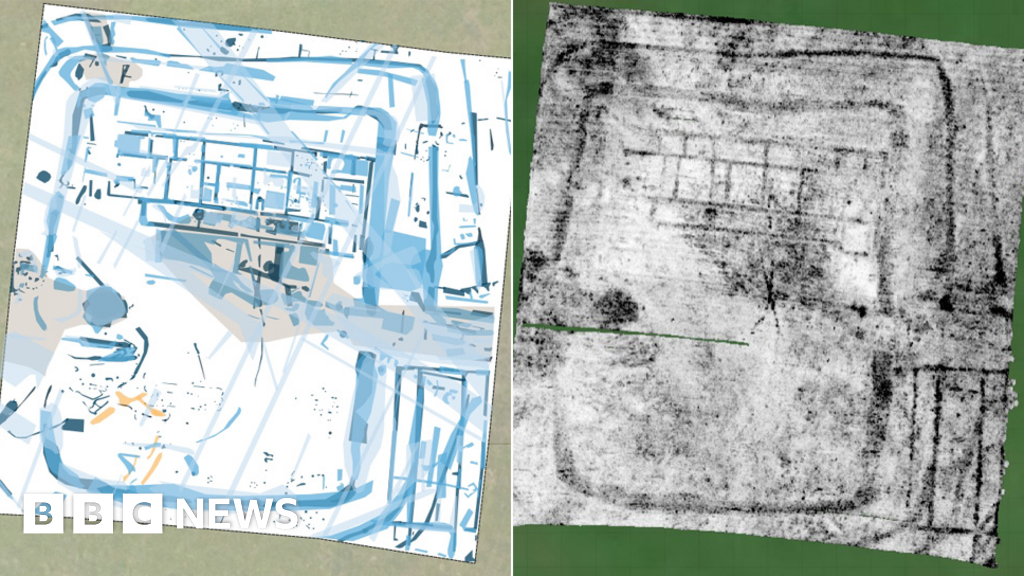

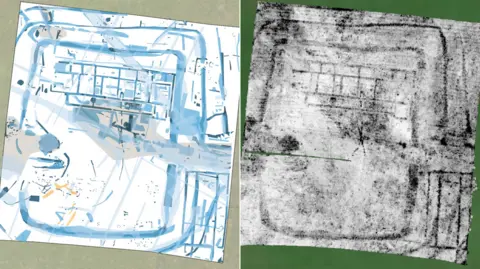

The groundbreaking findings were shared exclusively with BBC News ahead of a public announcement, underscoring the magnitude of the discovery. Geophysical surveys of Margam Country Park, a beloved visitor attraction nestled in south Wales, were initially commissioned as part of a broader community engagement initiative. The "ArchaeoMargam" project aimed to involve local school pupils and residents in learning more about their area’s rich heritage, using non-invasive scanning devices to map potential archaeological features hidden beneath the ground. What began as an educational endeavor soon turned into an archaeological triumph when the team "struck gold," uncovering the distinct footprint of a substantial Roman villa, spanning an impressive 572 square metres, enclosed within its own fortifications.

Dr. Langlands described the newly identified structure as a "really impressive and prestigious" building, indicative of considerable wealth and status. He speculated that it would likely have been adorned with fine decorations, including elegant statues and intricate mosaic floors, reflecting the sophistication of its inhabitants. The scans reveal what appears to be a "corridor villa with two wings and a veranda running along the front," a common and grand architectural style for Roman villas of high standing. Measuring approximately 43 metres (141 feet) in length, the villa’s layout suggests a complex interior, featuring "six main rooms [to the front] with two corridors leading to eight rooms at the rear." This elaborate design points to the residence of a "major local dignitary," someone of significant influence and power during the Roman occupation. Langlands painted a picture of a bustling estate, describing it as "quite a busy place – the centre of a big agricultural estate and lots of people coming and going," highlighting its role as a hub of economic and social activity.

As a standalone structure, this Margam villa now holds the distinction of being the largest Roman villa ever discovered in Wales. This is particularly significant because the majority of known Roman remains in Wales have typically been military camps and forts, reflecting the region’s frontier status within the Roman Empire. The discovery of such a grandiose and sophisticated rural estate challenges previous assumptions about Roman Wales. Dr. Langlands asserted that this find would compel experts to "rewrite the way we think about south Wales in the Romano-British period." He passionately argued against the notion of this part of Wales being merely "some sort of borderland, the edge of empire." Instead, he emphasized that "there were buildings here just as sophisticated and as high status as those we get in the agricultural heartlands of southern England." This revelation elevates Margam’s historical standing, suggesting that the area, which "may even have lent its name to the historic region of Glamorgan," was in fact "one of the most important centres of power in Wales."

Christian Bird of TerraDat, the Welsh firm responsible for conducting the geophysical surveys, lauded the clarity of the imaging. He noted that the images were "remarkably clear, identifying and mapping in 3D the villa structure, surrounding ditches and wider layout of the site." Beyond the main villa, the scans also revealed another substantial structure: a 354 square metre aisled building situated to the south-east. The team speculates that this secondary building could have served as a large barn, vital for the agricultural operations of the estate, or perhaps as a communal meeting hall, catering to the needs of the villa’s inhabitants and the wider community linked to the estate. This further underscores the complexity and importance of the entire Roman settlement at Margam.

To protect this invaluable archaeological site from potential damage or looting by "rogue metal detectorists," the exact location of the villa is being kept confidential for the time being. The priority now, according to Dr. Langlands, is the conservation of the site. This will be followed by further detailed survey work to gather more information, and then a concerted effort to secure funding for future excavation. Langlands playfully, yet justifiably, suggested the site had the potential to be "Port Talbot’s Pompeii." While acknowledging that "a lot of archaeologists get wound up by connections made with Pompeii," he believes the comparison is "in part justified because of the levels of preservation here." He elaborated, pointing to the survey data and the centuries of the land serving as a deer park, which meant it "hasn’t been subject to the type of ploughing [that has damaged many other villa sites]." This remarkable state of preservation offers "a really exciting prospect that we’ve got really good survival of archaeological evidence and the potential therefore to tell a huge amount about what life was like back in the first, second, third, fourth and maybe even into the 5th Century."

Further details of the team’s groundbreaking findings are set to be shared with the public at an open day hosted at Margam Abbey Church on January 17th. The news has already resonated deeply within the local community. Margaret Jones, a retired teacher from Port Talbot with a profound interest in local history, expressed her overwhelming excitement after booking a ticket for the event. "I’m still a bit shellshocked at the thought that this place where I played, where my children and grandchildren have played – that under our feet was this incredible house," she shared, adding, "It’s out of this world." She also highlighted the significant morale boost this discovery brings to Port Talbot, a town that has faced "so many disappointments" in recent years, particularly with "major job losses at the local steelworks." Jones believes this find "will put us on the map… and we’ll be proud."

Harriet Eaton, the Heritage Education Officer for Neath Port Talbot Council, who also runs a Young Archaeologist Club, described the discovery as "just incredible" and "something we couldn’t dream of." She expressed her fervent hope for a "community excavation" at the site in the future, which would offer local residents "that hands-on connection to the history unveiling beneath us." This sentiment reflects the broader aim of the UK government-funded ArchaeoMargam project, which has already seen school pupils actively involved in excavating land to the west of Margam Abbey Church, fostering a new generation’s interest in their historical landscape.

Margam Country Park, owned and managed by the local council, was already celebrated for its rich historical tapestry, boasting an Iron Age hillfort, the evocative remains of a 12th Century abbey, and an impressive Victorian castle among its many attractions. However, the Roman villa find fills "a big gap in our knowledge" regarding the activities and settlements in Margam during the Roman period, as articulated by park manager Michael Wynne. He emphasized the "really unusual find this far west and of such a significant size," affirming that it "will really add to our knowledge of Welsh and local history." Wynne optimistically concluded that the discovery promises to mean "more visitors to Margam Park, to Neath Port Talbot and to Wales generally," hailing it as "a really good news story" for the entire region.