The great debate about whether the NHS should use magic mushrooms to treat mental health is unfolding against a backdrop of increasing mental health challenges and a growing appetite for innovative therapeutic solutions. As traditional treatments often fall short for many, the potential of psychedelic substances like psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, is being revisited by the scientific community, sparking a complex discussion among doctors, regulators, and politicians about their place within mainstream healthcare.

Larissa Hope truly believes that psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, saved her life. Her journey began at 17, when a role in the popular TV drama Skins catapulted her into the public eye. While a dream for many, the sudden fame unexpectedly triggered deeply buried trauma, leading to profound psychological distress and suicidal ideation. Traditional antidepressants proved ineffective for Larissa, offering little relief from her escalating mental health crisis. It was a single, carefully controlled dose of psilocybin, administered under strict clinical supervision and integrated with therapy, that marked a dramatic turning point. "When I experienced it, I burst out crying," she recalls today. "It was the first time in my life I had ever felt a sense of belonging and safety in my body. I kept saying, ‘I’m home, I’m home’." This profound sense of inner peace and acceptance, achieved through the psychedelic experience, allowed her to process her trauma and, alongside continued therapeutic support, helped her confront and ultimately overcome her suicidal feelings. Nearly two decades later, Larissa remains a testament to its transformative power.

However, not everyone’s experience aligns with Larissa’s profoundly positive outcome. Jules Evans, a university researcher, recounts a dramatically different first encounter with psychedelics. At 18, he took LSD recreationally, an experience that quickly spiralled into what he describes as a "deluded" state. "I believed that everyone was talking about me, criticising me, judging me," he explains, detailing the terrifying paranoia that consumed him. "I thought, I’ve permanently damaged myself; I’ve permanently lost my mind. It was the most terrifying experience of my life." The repercussions were long-lasting; for years afterwards, he grappled with severe social anxiety and debilitating panic attacks, eventually receiving a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Today, Jules directs the Challenging Psychedelic Experiences Project, an initiative dedicated to supporting individuals who encounter difficulties after taking psychedelics, highlighting the critical need to acknowledge and address the potential adverse effects. These two starkly contrasting narratives — one of profound healing, the other of enduring trauma — underscore the complex dilemma now confronting medical professionals and policymakers: should treatments involving magic mushrooms and other potentially therapeutic psychedelic drugs be integrated into mainstream medical practice, specifically within the NHS?

The question has gained significant momentum amid a surge of new scientific studies suggesting that psychedelic drugs could offer breakthrough treatments for a range of severe mental health conditions, including major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD, complex trauma, and various addictions such as alcohol and gambling. Currently, the use of psychedelic medicine remains illegal outside of authorised research and clinical trials, classified under Schedule 1 of the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001, which designates substances with "no medicinal value." Despite this stringent classification, over 20 clinical trials have been launched since 2022, investigating various psychedelic medicines for conditions like depression, PTSD, and addiction. While many of these studies have yielded promising results, suggesting significant therapeutic benefits, others have presented mixed or unclear findings, and a few have shown no benefit on their primary measures. The scientific community eagerly awaits the results from one of the largest ongoing clinical trials into the use of psilocybin, conducted by UK biotech firm Compass Pathways, expected later this year. This data is crucial as the UK’s medicines regulator evaluates whether to ease current tight restrictions and permit the use of psychedelic medicine beyond research and trials.

Prof Oliver Howes, chair of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Psychopharmacology Committee, expresses cautious optimism regarding psychedelics as a potential new treatment for psychiatric disorders, including for NHS patients. He acknowledges the urgent need for "more treatments and better treatments for mental health disorders," particularly highlighting the "really interesting" promise shown in small-scale studies and their potential for quicker action compared to conventional therapies. However, he stresses the paramount importance of robust evidence from large-scale trials, warning against "overhyping the potential benefits." This caution is echoed by a report published by the Royal College of Psychiatrists in September 2025, which underlined the potential dangers of psychedelics and reiterated that taking these drugs outside of supervised clinical settings is not only illegal but can also be harmful.

The use of psychoactive substances for both recreational and ritualistic purposes is as old as civilisation itself, with magic mushrooms, opium, and cannabis having a long history across various cultures. In the 1960s and 1970s, substances like LSD, or "acid," became synonymous with the counterculture movement. Figures like Harvard psychologist Timothy Leary famously urged young people to "turn on, tune in, drop out" – advocating for them to awaken their inner potential, become aware of societal issues, and disengage from conventional social norms. However, this period also saw psychedelics become increasingly associated with social unrest and moral decline. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, these drugs were banned, leading to severe restrictions on scientific research into their potential therapeutic applications.

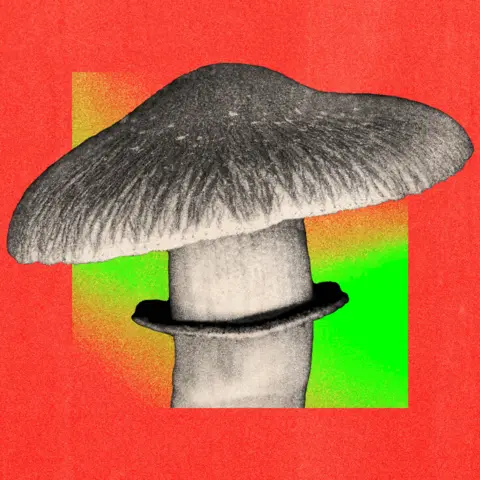

A turning point arrived in the 2010s with groundbreaking scientific developments spearheaded by Prof David Nutt and his team at Imperial College London. Their research began to challenge the prevailing view of psychedelics. Early clinical trials involving depressed patients suggested that psilocybin could be at least as effective as conventional antidepressants, with the added benefit of fewer reported side effects. Prof Nutt highlighted another significant advantage: its rapid action. "We thought rather than wait for eight weeks for antidepressants to switch off the part of the brain associated with depression, maybe psilocybin could switch it off in the space of a few minutes," he explained, suggesting a novel mechanism for alleviating depressive symptoms. This perspective, while scientifically promising, has not been universally embraced without debate. Prof Nutt, a respected scientist, has generated controversy in the past; he was notably dismissed in 2009 as chair of the government’s drugs advisory body, the Advisory Committee on the Misuse of Drugs, by then-Labour Home Secretary Alan Johnson. This dismissal followed public comments, such as his assertion that there was "not much difference" in harm caused by horse-riding and ecstasy, which were deemed incompatible with his role as a government adviser. Nevertheless, Prof Nutt’s pioneering studies ignited a global resurgence of interest in the therapeutic potential of various psychedelic drugs, sparking numerous investigations worldwide.

At University College London, neuroscientist Dr Ravi Das is leading research into the neurobiological underpinnings of addiction, exploring why some habits become entrenched while others dissipate. He believes psychedelics may hold the key to understanding and treating these conditions. His current study recruits heavy drinkers to investigate whether dimethyltryptamine (DMT), a short-acting psychedelic also used recreationally, can specifically target the brain’s memory and learning systems. This research builds upon existing evidence suggesting that psilocybin can disrupt the habitual behaviours and learned associations central to addiction. "Every time someone drinks, a bit like Pavlov’s dog, you’re learning to associate things in the environment with the rewarding effect of alcohol," Dr Das explains. "We’ve been focusing on whether certain drugs, such as psychedelics, can break down those associations." This is an early-stage study, but if successful, and with regulatory approval, the ultimate aim is to make such treatments available through the NHS. Dr Das argues passionately for equitable access: "If psychedelic therapies prove to be both safe and more effective than current treatments, I would hope to see them made accessible via the NHS – rather than to just the privileged few who can afford them privately."

The legal landscape for psychedelics is complex. Ketamine, which Dr Das has also studied, occupies a different legal category and can already be used as part of medical treatment in the UK. However, other potent psychedelics like DMT, LSD, psilocybin, and MDMA are currently deemed to have no legitimate medical use, placing them under the strictest controls and limiting their use exclusively to research settings, even then requiring extremely difficult-to-obtain medical licenses. Dr Das remains hopeful that mounting scientific evidence from robust trials will eventually shift government views. "I hope if there’s sufficient evidence, the government will be open to revising the scheduling of these drugs," he states.

However, an analysis published in the British Medical Journal in November 2024 by PhD student Cédric Lemarchand and his colleagues urged greater scrutiny. They questioned the ease of determining the precise effects of psychedelic drugs, noting: "Because hallucinogens are often combined with a psychotherapy component, it is difficult to separate the effects of the drug from the therapeutic context, complicating comprehensive evaluations and product labelling." The analysis also raised concerns about the limitations of short-term trials, which "may not detect the potential for harm and serious adverse events from long-term use of hallucinogens… The potential for abuse or misuse must also be considered." They advocated for medical journals to "appraise the evidence more critically, fully account for limitations, avoid spin and unsubstantiated claims, and correct the record when needed" to ensure rigorous vetting before endorsing hallucinogens as safe and effective treatments.

Despite the growing research, doctors like Prof Howes maintain a cautious stance. He firmly believes that, with the exception of ketamine (which has already undergone regulatory assessment), psychedelic treatments should not become routine medical practice in the UK outside of carefully controlled research settings. This position will hold until larger, more rigorous trials can provide robust evidence for both their safety and effectiveness. "In a clinical trial setting, it’s very carefully evaluated. If people take these on their own or in a backstreet clinic, then there is no guarantee of that and the safety issues start becoming a major issue," he warns. His concerns are substantiated by data from various studies collected by the Challenging Psychedelic Experiences Project, which indicates that 52% of regular psychedelic users reported experiencing an intensely challenging trip, with 39% considering it "one of the five most difficult experiences of their life." Furthermore, 6.7% admitted to considering harming themselves or others following a challenging experience, and 8.9% reported being "impaired" for more than a day after a difficult trip. Jules Evans highlights that some individuals even required medical or psychiatric assistance and continued to feel worse for weeks, months, or even years after their experience. "Ideally, I would love doctors and regulators to know more about these adverse effects, and how people can recover from them, before they say, any of these therapies are safe," he argues.

Yet, figures like Prof Nutt, Prof Howes, and Dr Das contend that the advancement of these medicines into clinical practice is unduly hampered by the arduous process of obtaining permission for medically supervised clinical trials. "There are so many people suffering unnecessarily," Prof Nutt passionately told BBC News. "And some of them are dying, because of the unreasonable barriers to research and treatment that we face in this country. It is, in my view, a moral failing." He believes that once these medicines are unequivocally proven safe and effective, it is "vital they are made available through the NHS to all who need them, not limited to the private sector, as happened with medical cannabis." While urging caution, Prof Howes shares this sentiment, stating, "There are big barriers to doing this research, so we do ask for the government to review the regulations of these substances, for research, because it does lead to long delays, and, we desperately do need new treatments."

The Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs remains explicit, stating that Schedule 1 contains drugs "of no medicinal value," thus justifying the tightest controls. Ministers also link the Home Office licensing regime directly to public protection. In response, the government has supported plans to ease licensing requirements for some clinical trials approved by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency and Health Research Authority, with work ongoing to implement exemptions for certain universities and NHS sites. A cross-government working group is coordinating this cautious rollout, pending the results of pilot projects. However, some doctors, including Prof Howes, express frustration that these changes are moving "painfully slowly," noting that "there’s still a lot of red tape holding things up."

Supporters of psychedelic medicines hold out hope that the upcoming phase three trials by Compass Pathways will pave the way for further relaxations, at least for research purposes, and ultimately for broader clinical access. Larissa Hope’s concern remains squarely on those who find themselves in the desperate situation she once faced. "It is a reflection of society that psychedelic medicine is not more accessible as a treatment for everyone," she asserts. "It could stop so many premature deaths, as it did for me." The debate continues, balancing the immense potential for mental health breakthroughs against the imperative for rigorous safety, ethical considerations, and equitable access for all.