The Houses of Parliament, a globally recognised symbol of British democracy and an architectural marvel, is teetering on the brink of structural failure. For years, the Palace of Westminster has been plagued by a litany of decaying infrastructure, fire hazards, and health risks, pushing its occupants – MPs and peers – towards an inescapable decision. By early 2026, they are expected to be presented with a stark choice on how to undertake billions of pounds worth of essential maintenance work, a decision that could redefine the future of the UK’s legislative heart.

The urgency of the situation cannot be overstated. Lord Dobbs, the acclaimed writer of House of Cards and a peer himself, warns grimly that the building is "just waiting for some disaster." His macabre advice to visitors – "If they see somebody running please don’t stop to find out why they’re running, just follow them" – underscores the palpable sense of dread amongst those who work within its ancient walls. This sentiment is echoed by former Labour minister Lord Hain, who likens the impending catastrophe to "a Notre Dame inferno in the making," referencing the devastating fire that ravaged the Parisian cathedral in 2019. "The Commons could burn down at any time," he asserts, highlighting the very real threat of a catastrophic blaze consuming one of the world’s most iconic buildings.

Warnings about the Palace’s perilous state are not new. A parliamentary committee report published a decade ago, in 2014, sounded a dire alarm, cautioning that the Palace of Westminster "faces an impending crisis which we cannot responsibly ignore." The report unequivocally stated that "Unless an intensive programme of major remedial work is undertaken soon, it is likely that the building will become uninhabitable." Despite these stark warnings, a definitive decision has been repeatedly postponed, a political hot potato passed down through successive governments and parliaments. However, the escalating frequency of alarming incidents – from literal falling masonry, posing a direct threat to safety, to the persistent problem of lingering asbestos, a long-term health hazard, and recurring small fires within the labyrinthine structure, not to mention the ignominious reports of "exploding toilets" – has made further delay untenable. There is now a rare, if unsettling, consensus that the work must be done. The challenge, however, lies not in the "what," but in the "how."

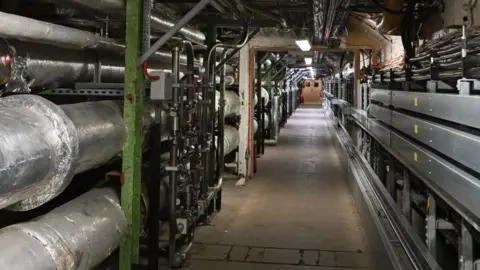

The Palace of Westminster, a Grade I listed building and a UNESCO World Heritage site, is a complex beast. Its Victorian Gothic grandeur conceals an outdated, intricate network of services, many dating back to its post-1834 fire reconstruction. The image of a hot, fusty basement corridor, choked with hundreds of tangled gas pipes, water mains, and electrical wires – some redundant, some dangerous, all in desperate need of replacement – paints a vivid picture of the scale of the challenge. One particular pipe, embossed with the year 1945, epitomises the problem: decommissioned yet inextricably entwined with active systems, its removal would necessitate a complete shutdown of entire sections of the building. This antiquated infrastructure is not merely an inconvenience; it’s a ticking time bomb.

In the early weeks of 2026, parliamentarians will finally be confronted with a formal presentation of three primary options for carrying out the monumental restoration work. These options represent varying degrees of disruption, cost, and duration, each with its own proponents and detractors.

The first, and arguably most radical, option is a full decant. This would involve both the House of Commons and the House of Lords completely vacating the Palace for the duration of the works. Potential alternative locations for a decanted Parliament have been mooted, including the nearby QEII Conference Centre, Richmond House in Whitehall, and even the more audacious suggestion of a floating barge on the Thames. A previous report from 2022 estimated that a full decant could cost between £7 billion and £13 billion, with the building entirely vacated for an intensive period of between 12 and 20 years. Proponents argue this is the most efficient and ultimately cost-effective approach, allowing for comprehensive and faster restoration without the complexities of working around an active legislature.

The second option, a partial decant, would see MPs remain within the Palace but relocate their sittings to the House of Lords chamber, while peers would move to an external location. This hybrid approach aims to maintain a parliamentary presence within the historic confines, but comes with significant drawbacks. The 2022 report suggested that keeping MPs in Parliament in this manner would prolong the works by an additional seven to 15 years, pushing the total project timeline to potentially 27 to 35 years, and inflate costs substantially to an estimated £9.5 billion to £18.5 billion. The logistical nightmare of operating a major construction site around a functioning parliamentary estate, even partially, is immense.

The third, and most protracted, option involves allowing the House of Commons to operate throughout the works, with phased restoration in sections. This ‘stay-and-play’ approach, while appealing to those reluctant to leave the historic chambers, carries the highest penalties. Estimated to increase the project duration by a staggering 27 to 48 years, it would boost costs by approximately 60% compared to a full decant, potentially reaching an eye-watering £11 billion to £22 billion. The sheer inefficiency of this method, with constant starts, stops, and relocations of parliamentary activities, makes it the most expensive and time-consuming, raising questions about its long-term viability and public acceptance.

The upcoming report from the Renewal and Restoration Client Board, a body comprising MPs, peers, and independent lay members, is expected to provide updated costs, risks, and benefits for each of these options. Crucially, it will also include a recommendation for what the board deems the "best," or perhaps "least painful," choice. Once this report is submitted and the government schedules a vote, the ultimate decision will fall to MPs and peers, who must weigh the historical significance, practical implications, and immense financial burden of each path.

Lord Hain is a staunch advocate for a full decant, reiterating that previous analyses consistently identified it as the more cost-effective and efficient solution in the long run. He also points to a significant historical precedent: in 2018, MPs narrowly voted to accept the principle of fully vacating the building. However, subsequent concerns regarding the spiralling costs and the sheer upheaval of such a move led to a rethink, culminating in the establishment of the current Restoration and Renewal Client Board to re-examine all possibilities. Lord Hain expresses profound exasperation at these delays, lamenting, "It’s a terrible advertisement for parliamentary democracy." He warns of public outrage should a disaster strike: "People would be horrified if it [Parliament] fell apart in a raging fire… and then I think that the focus would be back on the politicians who dodged and weaved and backslid and kicked the can down the road." For him, the time for prevarication is over: "It’s got to be done now and it’s got to be done properly." Baroness Smith, the government’s most senior minister in the House of Lords, aligns with this view, telling Radio 4’s Westminster Hour that she believes there is "no decant-free option" and explicitly stating her preference for both houses to move out. "The amount of money spent keeping the building going in a poor condition would be better spent getting the building into a good condition," she argues, framing it as a pragmatic financial decision.

However, not all parliamentarians share this enthusiasm for a full decant. Conservative peer Lord Dobbs voices profound reservations about parliamentarians leaving the building. "Are we going to take a great holiday from Parliament and democracy while the builders get this done?" he questions, highlighting a concern about the potential erosion of democratic accountability. His fears are particularly acute for the House of Lords. While acknowledging the chamber does "an exceptional job," he candidly admits its unpopularity with the wider public. "Unless we can turn that lack of understanding and unpopularity around, it’s very possible that we will go off to the QEII Conference Centre and never come back," he warns. "It will be the end of the House of Lords – an expert will simply put a line through on a piece of paper and just rub us out." For Lord Dobbs, the physical presence within the Palace is inextricably linked to the Lords’ legitimacy and influence: "Moving us out I think is going to cut off so much of our credibility and authority and our ability to do anything at keeping the government and the House of Commons under some sort of control."

Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg, who as a senior minister between 2019 and 2022 was partly involved in initiating the rethink of the options, remains deeply sceptical of both the estimated costs of operating Parliament during works and the alarmist predictions of imminent structural collapse. "I was on the committee that looked into it in the 2010-2015 Parliament, when we were told that the whole place would be ruined if we didn’t act immediately," he recounts. "And here we are 10 years or more later – we haven’t acted immediately and the place still seems to be standing." He robustly defends his decision to block the previous plans, dismissing them as "crazy, over-elaborate and too expensive." Like Lord Dobbs, Sir Jacob does not support a full decant, instead advocating for the work to be completed in stages. His reasoning is rooted in a distrust of cost projections once a building is fully vacated: "Once you move out that’s when the builders really have you and that’s when the prices go up." While acknowledging that the basement of Parliament "looks pretty chaotic," he adds, "The people who operate it know how it works," implying that the current system, however messy, is functional and understood by its custodians.

Regardless of the chosen option, the British taxpayer is facing a bill running into many billions of pounds. This financial reality weighs heavily on parliamentarians, particularly newer arrivals. Jayne Kirkham, a Labour MP elected in 2024 for Truro and Falmouth, offers a tangible insight into the current conditions. Her office, situated beneath the Speaker’s House, is plagued by "gents’ toilets" that are "regularly exploding with sewage." While acutely aware of the urgent need for repairs, she acknowledges the dilemma: as a new MP, there are "a million things that I want to be doing for Truro and Falmouth" and fixing the building is not at the "absolute top of the priority list." Yet, she also feels a profound sense of duty: "This is an amazing building – we’re so privileged to have it. It’s iconic and for anything to happen to it would be terrible." For Kirkham, if a full decant means the work can be done more safely and for less money, "that would seem like the most sensible option."

However, not all new MPs are so traditional in their outlook. Edward Morello, a Liberal Democrat MP from the 2024 intake, took to social media to express a more radical "unpopular opinion": "Move us out permanently. Make it a museum." This provocative suggestion highlights the deep divisions and unconventional thinking now emerging in the debate.

The year 2026 looms as a critical juncture. After decades of discussion, delays, and mounting disrepair, MPs and peers will finally be forced to confront the monumental task of preserving one of the nation’s most cherished and vital institutions. The decision they make will not only impact the functional future of British democracy but will also leave an indelible mark on the historical legacy of the Palace of Westminster for generations to come.

You can listen to the interviews on BBC Radio 4’s Westminster Hour at 2200 BST on Sunday and then on BBC Sounds.

Sign up for our Politics Essential newsletter to read top political analysis, gain insight from across the UK and stay up to speed with the big moments. It’ll be delivered straight to your inbox every weekday.