By Justin Rowlatt, Climate Editor, and Matt McGrath, Environment correspondent

In three decades of these annual gatherings aimed at forging global consensus on how to prevent and deal with global warming, COP30 in Belém, Brazil, will undoubtedly go down as among the most contentious and deeply divisive. The summit concluded on a Saturday that left many countries livid, as the final agreement contained no explicit mention of the fossil fuels universally acknowledged as the primary drivers of atmospheric heating. Conversely, other nations, particularly those with significant economic stakes in the continued production of oil, gas, and coal, felt a sense of vindication, interpreting the outcome as a tacit acceptance of their energy transition timelines. This summit served as a stark reality check, exposing the widening chasm in global consensus regarding the urgency and methodology of addressing climate change. Its proceedings underscored a fundamental breakdown in the collective will that once propelled significant agreements like the Paris Accord. Here are five key takeaways from what some participants have ominously dubbed the "COP of truth."

Brazil – Not Their Finest Hour

While the most crucial outcome from COP30 is arguably that the global climate ‘ship’ remains afloat, with the multilateral process intact, the journey through Belém was far from smooth. Many participants departed profoundly unhappy, having failed to secure anything close to their desired outcomes. Despite a palpable sense of warmth and appreciation for Brazil as the host nation, and for its President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, there was considerable frustration regarding the stewardship of the meeting.

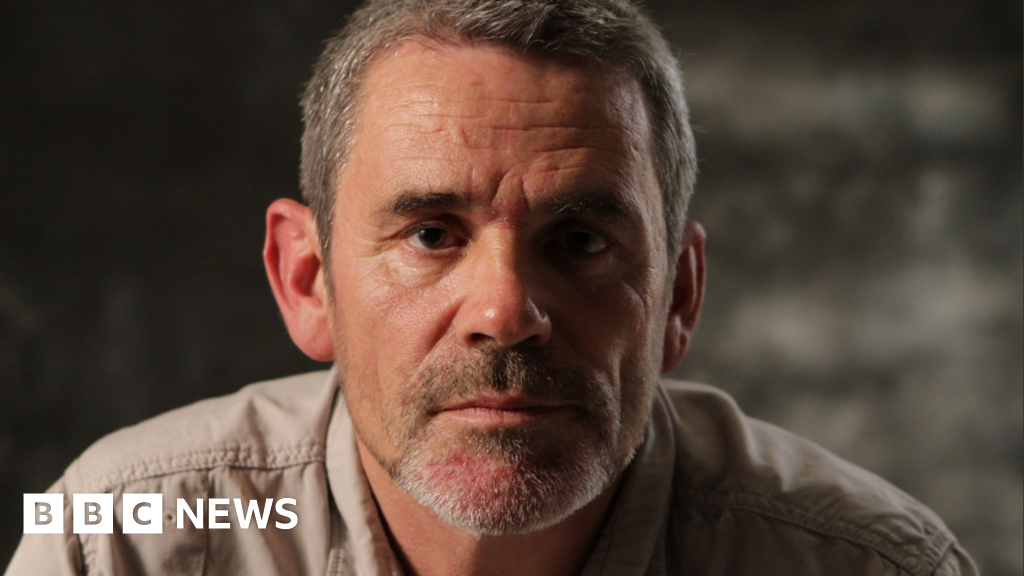

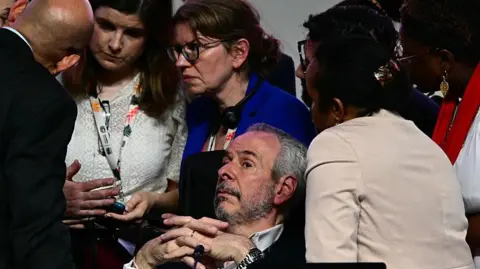

Right from the outset, a significant ideological gulf appeared to exist between President Lula’s ambitious vision for the summit and what COP President André Corrêa do Lago deemed pragmatically achievable within the delicate framework of international consensus. Lula, known for his strong environmental rhetoric, spoke passionately of clear roadmaps away from fossil fuels during pre-COP meetings with a handful of world leaders who arrived early in Belém. This idea resonated with several countries, including the UK, and within days, a concerted campaign emerged to formally integrate this roadmap concept into the official negotiation texts.

However, Do Lago, with his unwavering commitment to consensus, was notably unenthusiastic. He understood that forcefully injecting the contentious issue of a fossil fuel phase-out onto the core agenda would inevitably rupture the fragile unity he sought to preserve. Initial draft texts for the final agreement did contain some vague references that hinted at a roadmap, but these were swiftly removed within days, never to reappear in any substantive form.

A coalition of around 80 countries, spearheaded by Colombia and the European Union, desperately tried to reintroduce language that would signal a stronger, more decisive step away from coal, oil, and gas. In an attempt to foster consensus, do Lago convened a ‘mutirão’ – a traditional Brazilian group discussion format designed for collective problem-solving. Yet, this initiative, intended to bridge divides, only exacerbated them. Negotiators from key Arab nations steadfastly refused to engage in huddles with those advocating for a fossil fuel pathway. The European Union’s appeals were met with a blunt and often dismissive reception from major oil-producing nations. "We make energy policy in our capital not in yours," a Saudi delegate reportedly declared to the EU team in a tense closed-door meeting, a remark that encapsulated the deep divisions.

The chasm proved unbridgeable, pushing the talks to the brink of collapse. In a last-ditch effort to salvage the summit and provide a face-saving mechanism, Brazil proposed the creation of separate roadmaps on deforestation and fossil fuels that would exist outside the formal COP agreement. These external initiatives were met with hearty applause in the plenary halls, offering a glimmer of progress, but their legal standing and enforceability remain highly uncertain. Brazil’s dual identity as a crucial Amazon protector and a nation with aspirations for increased oil production undoubtedly complicated its hosting role, creating inherent tensions that ultimately undermined its ability to steer the summit toward a more ambitious outcome on fossil fuels.

EU Had a Bad COP

Despite being the richest bloc of nations still fully committed to the Paris Agreement, COP30 was arguably not the European Union’s finest hour. While the EU has consistently presented itself as a leader in climate ambition, grandstanding on the urgent need for a fossil fuel roadmap, their tactical missteps left them cornered on another critical aspect of the agreement.

Early drafts of the summit text included the significant idea of tripling financial support for climate adaptation in developing countries. This ambitious goal survived into the final draft, albeit with vague wording that initially prevented the EU from objecting too strenuously. Crucially, the "tripling" target itself remained firmly embedded in the text. This seemingly minor detail had profound implications for the EU’s negotiating leverage.

When the EU later attempted to press developing nations to support their push for a fossil fuel roadmap, they found themselves without a valuable bargaining chip to sweeten the deal. The "tripling" concept, which would typically be a powerful incentive for developing nations, was already "baked in" to the agreement. This meant the EU had already given away a key concession without securing anything in return on their primary agenda item.

Li Shuo, a veteran observer of climate politics from the Asia Society, noted, "Overall we are seeing a European Union that has been cornered. This partly reflects the power shift in the real world, the emerging power of the BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, India, China) and BRICS countries, and the relative decline of the European Union’s influence." The EU, typically a formidable negotiating force, found its efforts to push for stronger fossil fuel language largely thwarted. Apart from a minor victory in shifting the deadline for tripling finance from 2030 to 2035, they were largely compelled to accept the final deal, achieving very little tangible progress on their core demand for a fossil fuel phase-out. This outcome underscores the complex and shifting dynamics of global climate diplomacy, where economic and geopolitical realities increasingly shape negotiating outcomes.

Future of COP in Question

Throughout the two weeks in Belém, a persistent and increasingly urgent question echoed through the conference halls: what is the future of the COP ‘process’ itself? Two often-heard, critical perspectives highlighted the growing disillusionment.

Firstly, many questioned the sheer logistical and environmental absurdity of flying thousands of delegates, activists, journalists, and observers halfway around the world to convene in enormous, energy-intensive, air-conditioned tents. Their purpose, it seemed, was often to engage in protracted debates over the minutiae of commas, prepositions, and interpretations of convoluted legalistic language. Secondly, the criticism extended to the seemingly ridiculous reality that the most critical discussions – those concerning the very future of how humanity will power its world and sustain its existence – frequently occurred in the early hours of the morning, among sleep-deprived delegates who had been away from home for weeks, often compromising the quality and fairness of decisions.

The COP framework, born out of a different geopolitical era, served the world exceptionally well in ultimately delivering the landmark Paris Climate Agreement a decade ago. However, many participants now feel that it no longer possesses a clear, powerful, or universally accepted purpose. "We can’t discard it entirely," Harjeet Singh, an activist with the Fossil Fuel Treaty Initiative, told BBC News, "But it requires retrofitting. We will need processes outside this system to help complement what we have done so far." This sentiment reflects a growing belief that the current, consensus-driven model struggles to adapt to the fragmented and increasingly contentious global landscape.

The intertwined challenges of escalating energy costs and the complex pathways countries must navigate to achieve net-zero emissions have never been more critical or directly impactful on billions of people’s daily lives. Yet, the current COP model often feels profoundly detached from these realities. It is a consensus process inherently designed for a world that no longer exists, one less fractured by competing national interests and geopolitical rivalries. Brazil, as host, recognized some of these issues, attempting to brand COP30 as an "implementation COP" and placing significant focus on an "energy agenda." However, these concepts remained largely abstract, failing to provide the concrete direction or revitalized purpose that many felt was desperately needed. The message from Belém is clear: COP leaders must urgently read the room and find a new, more effective approach, or these vital conferences risk losing all relevance and efficacy in the face of an accelerating climate crisis.

Trade Comes in From the Cold

For the first time in the history of these climate talks, global trade emerged as one of the most significant and hotly contested issues. According to veteran COP-watcher Alden Meyer of the climate think-tank E3G, there was an "orchestrated" effort to raise trade-related concerns in virtually every negotiating room, signaling a new front in climate diplomacy.

Many observers might wonder about the connection between trade and climate change. The answer lies in the European Union’s ambitious plans to introduce a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). This mechanism proposes a border tax on imports of certain high-carbon products, including vital industrial goods like steel, fertilizers, cement, and aluminum. Predictably, this move has drawn considerable ire from many of the EU’s major trading partners, notably China, India, and Saudi Arabia.

These nations argue that the CBAM is an unfair imposition by a powerful trading bloc, constituting a "unilateral" measure that will render their goods sold into Europe more expensive and, consequently, less competitive. They view it as a protectionist tariff disguised as an environmental policy.

The Europeans, however, vigorously defend their stance, asserting that the measure is not about stifling trade but about genuinely cutting planet-warming gases and tackling climate change. They point out that their own domestic producers of these materials already face significant fees for the carbon emissions they generate under the EU’s Emissions Trading System. The CBAM, they argue, is designed to level the playing field, protecting European industries from "carbon leakage" – the phenomenon where production shifts to countries with less stringent climate policies – and ensuring that less environmentally friendly, cheaper imports do not gain an unfair advantage. Their message to trading partners is direct: if you wish to avoid our border tax, simply implement your own emissions fees on your polluting industries and collect the revenue yourselves.

Economists largely support this approach, as making pollution more expensive is a powerful incentive for industries to transition to cleaner energy alternatives and more sustainable production methods. While this inevitably means consumers might pay more for goods produced with carbon-intensive materials, the long-term benefits for climate action are considered substantial.

The issue, highly contentious and complex, was ultimately resolved in Brazil through a classic COP compromise: rather than a definitive agreement, the discussions were deferred to future talks. The final agreement launched an ongoing dialogue on trade, explicitly mandating its continuation in future UN climate talks and involving a broader range of actors, including governments and the World Trade Organization. This step, while not a resolution, signifies a crucial recognition of the inextricable link between global trade and climate policy, ensuring it will remain a central feature of future negotiations.

Trump Gains by Staying Away – China Gains by Staying Quiet

The world’s two largest carbon emitters, China and the United States, exerted similar, if contrasting, impacts on COP30, achieving their influence through vastly different approaches.

On the American front, the absence of US President Donald Trump from the summit was more than symbolic; it had tangible repercussions. His known skepticism towards aggressive climate action emboldened his allies within the negotiations. Russia, typically a relatively quiet participant in these summits, stepped conspicuously to the fore, actively blocking efforts to establish clear fossil fuel roadmaps. While major oil producers like Saudi Arabia predictably adopted a hostile stance towards curbing fossil fuels, the US’s broader stance under Trump implicitly provided cover and encouragement for such resistance. The lack of a strong, unified pro-climate message from one of the world’s largest economies and historical emitters undoubtedly weakened the overall ambition of the summit.

Meanwhile, China, the other colossal emitter, pursued a vastly different strategy: it stayed remarkably quiet on the political front, concentrating instead on strategic economic maneuvers. "China kept a low political profile," observed Li Shuo from the Asia Society. "And they focused on making money in the real world." This approach allowed China to avoid direct confrontation over contentious issues like fossil fuel phase-outs, while simultaneously solidifying its dominant position in the burgeoning global renewable energy sector.

Experts argue that the long-term business deals China is actively pursuing will ultimately eclipse the US’s continued efforts to promote and sell fossil fuels globally. Solar energy, for instance, has become the cheapest source of electricity in many parts of the world, and China utterly dominates its manufacturing and deployment. "Solar is the cheapest source of energy, and the long-term direction is very clear," Li Shuo emphasized. "China dominates in this sector, and that puts the US in a very difficult position." This quiet, strategic accumulation of economic power in the green energy transition represents a profound and lasting gain for China, subtly but fundamentally reshaping the global energy landscape. While the US under Trump might have aimed to preserve the fossil fuel economy, China is strategically positioning itself to lead the post-fossil fuel era, making its understated presence at COP30 a powerful, albeit indirect, form of influence.