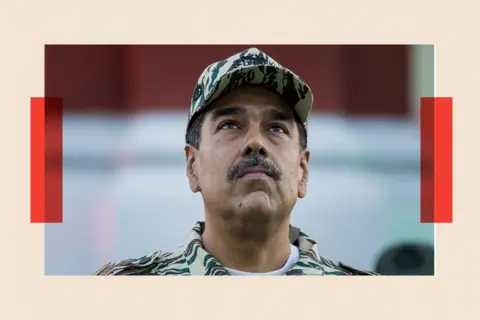

"Keir can’t be the last gasp of the dying world order," warns a prominent minister, encapsulating a growing anxiety within Westminster as Prime Minister Keir Starmer navigates a rapidly shifting global landscape. His premiership finds itself at the crucible of international relations, where the established norms are being fundamentally reshaped, largely by the unpredictable influence of his formidable counterpart in the White House. While domestic policy has presented a litany of challenges, the government’s handling of foreign affairs has, until recently, been broadly perceived as a point of strength. Yet, as Donald Trump’s global activities escalate, particularly his assertive moves in regions like Venezuela and his provocative claims over Greenland, Starmer’s increasingly emboldened domestic opponents are determined to transform this rare area of success into a fresh battleground.

The perceived closeness between Starmer and Trump has, predictably, stirred a degree of unease, particularly within the Labour Party’s left flank. This discomfort is not new; it is a recurring symptom of a traditional British distaste for the perceived ‘schmaltz’ of the "special relationship." History is replete with examples: Tony Blair famously faced accusations of being George W. Bush’s "poodle" over the Iraq War, and satirical caricatures of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan dancing together in the White House underscored similar sentiments of subservience. Whatever the personal chemistry, or lack thereof, between leaders, the "special relationship" has always been fundamentally transactional. As one seasoned Labour MP succinctly puts it, it’s "the unavoidable cost of doing business." The underlying calculus for Starmer’s government has been clear: demonstrate loyalty and foster friendship with a controversial American leader, and the dividends will follow. This might manifest as an easier path to securing a favourable trade deal than most other nations could hope for, or a more receptive ear to pleas for robust support for Ukraine, perhaps even facilitated by strategically dangled royal invites or a sympathetic stance towards the ambitions of powerful US tech firms.

To date, this pragmatic approach has largely been deemed successful, with senior government figures quietly crediting their foreign policy architect, Jonathan Powell – a veteran advisor from the Blair era – with "playing a blinder." However, this delicate balancing act is now showing signs of strain. A senior Labour MP articulates a burgeoning concern: the growing risk of "being linked to the madness" that emanates from the Trump administration. The Prime Minister now faces the uncomfortable prospect of being squeezed from both sides of the political aisle, accused of weakness by his domestic rivals, while simultaneously confronting a significant policy dilemma: the escalating question of defence spending.

Traditionally, the official opposition in the UK has tended to maintain a degree of consensus with the government on foreign policy matters. In the turbulent political climate of 2026, such traditions feel increasingly quaint. An increasingly confident Kemi Badenoch, a rising star within the Conservative Party, exemplifies this shift. She conspicuously broke with convention this week, launching an aggressive attack on the Prime Minister’s foreign policy in the House of Commons. Badenoch scorned Starmer for his perceived irrelevance, highlighting that he had spoken only to Trump’s senior advisors a full five days after the US strike on Venezuela, rather than directly to the President. She further lambasted him for withholding full details from MPs and the public regarding a sensitive deal with France and Ukraine that could potentially deploy UK troops on the ground in the event of a future peace agreement.

Badenoch’s team believes her parliamentary intervention successfully "punctured" Starmer’s authority on foreign policy, and observers can anticipate a sustained Conservative campaign to argue that the UK is failing to project sufficient strength on the global stage. This strategy, however, begs the crucial counter-question: what exactly would a Badenoch-led government do differently? It is far from a foregone conclusion that she would automatically gain access to Trump’s inner decision-making circle in a way Starmer has not. Would she be better placed to broker a lasting peace deal in Ukraine? Or would her administration simply double down on existing operations, such as the UK-supported seizure of the Marinera tanker in the North Atlantic this week, targeting Russia’s shadow fleet? In truth, the primary function of the opposition is to articulate arguments and scrutinise, not to dictate executive action.

The criticisms are not solely confined to the Conservative benches; a vigorous assault on Starmer’s foreign policy is also emanating from the left, both outside and within the Labour Party itself. The Liberal Democrats, currently polling within striking distance of Labour in certain areas, took the unusual step of dedicating both their questions at Prime Minister’s Questions this week to foreign affairs. Significantly, Lib Dem leader Ed Davey’s comments regarding Venezuela garnered nearly 10 million views on Instagram, outperforming all his previous posts – a telling indicator of how this issue is resonating with the public in an increasingly noisy media landscape.

With the frenetic pace of Trump’s foreign policy initiatives accelerating, a senior Liberal Democrat source sees a clear "opportunity." They contend that "Starmer is so closely hitched to Trump there’s a growing risk it’s damaging – and it works on the doors: lots of Labour voters are anti-Trump but pro-Nato." Sources within the party draw a parallel to their significant electoral breakthrough when they staunchly opposed Tony Blair over the Iraq War. While the historical analogy is not entirely pure, the palpable discomfort within Labour’s ranks is undeniable, and their rivals are keenly poised to capitalise.

The surging Green Party is also eager to harness public unhappiness over Trump to Starmer’s detriment. A senior Green Party source states unequivocally: "It’s hugely problematic for the prime minister. He’s put so many of our eggs in the Donald Trump basket. Lavishing him with a second state visit – to stroke his ego – was always going to end in tears." Within Labour, pockets of dissent persist on the party’s traditional left, with some MPs openly questioning the government’s muted condemnation of Trump’s actions against Venezuela and expressing unease following the UK’s backing of the Marinera tanker seizure. Even some supportive colleagues, who otherwise commend the Prime Minister’s actions on the world stage, voice concern about his domestic political messaging. "The responses have been the response of a diplomat’s brain, not a political one," observes one insider, adding, "and if you don’t take a strong political position too, you’ll be attacked by both sides."

Paradoxically, such visible international turmoil may, for now, make a leadership challenge to Starmer less likely. Any aspiring contender flirting with the idea of unseating him could appear self-indulgent or opportunistic when the global situation is in such precarious flux. Furthermore, foreign policy is not typically considered the strong suit of Labour’s main current antagonist, Reform UK. This makes it comparatively easier for Labour to parry criticisms on foreign policy from Reform than to fend off their relentless attacks on immigration.

Stepping beyond the immediate hurly-burly of party political attacks, the dramatic opening to the year on the international stage has brought into sharp focus a critical, recurring question: how much more taxpayer money will genuinely need to be allocated to defence in an increasingly unstable world, and has the government truly made the difficult decisions necessary to achieve this? "Defence spending is a proper wound now," one insider confided, "it’s not just the chiefs grumbling."

The question of how much to spend on national protection, and by when, was already a thorny issue. The Prime Minister frequently reiterates that the world is in "turbulent times," as he articulated in a recent lengthy interview. He firmly believes the UK and the rest of Europe must substantially increase their defence outlays. On Friday, the defence secretary, John Healey, responding to reports of significant shortfalls in available funds, reiterated that the evolving global situation demands a "new era for defence." Ministers have already pledged to increase defence spending at a rate not seen since the end of the Cold War – a promise, however, that comes with a significant caveat.

Before the turn of 2026, the former Chief of the Defence Staff, Sir Tony Radakin, publicly argued that existing budgets might not be sufficient to avoid cuts. The defence secretary swiftly countered this, claiming Radakin was mistaken. Yet, the following week, the new Chief of the Defence Staff confirmed that some cuts to specific capabilities had indeed already occurred. An awkward admission, to say the least. This internal spat, and the government’s ongoing major defence review, predated the United States’ new security strategy, which, in remarkably dramatic language, unequivocally laid bare the approach of the Trump White House. It also preceded the American strikes on Venezuela, which demonstrated Trump’s willingness to act decisively, not merely issue threats. And most astonishingly, it preceded the White House’s re-stated ambition this week to "possess Greenland," even hinting at the use of military force – a move that would target a member of the very defence alliance (NATO) that the US itself is sworn to defend.

Following Trump’s recent, startling actions, the question of the UK’s true willingness to pay for its own protection, and what politicians are prepared to sacrifice to make that a reality, grows more urgent by the day. Many, including some opposition parties, argue that ministers have already committed to spending more on defence. However, have ministers truly grasped the magnitude of the necessary shift, or honestly communicated it to the public? That remains a distinct and critical question.

A long-standing tenet of British politics dictates that voters generally do not base their electoral choices on foreign policy; domestic issues are almost invariably more important. As one government source put it: "People want to see us handle the foreign stuff competently but it’s not really what people care about – they only vote on foreign affairs grounds in genuinely exceptional circumstances." Yet, the opposition parties are now eager to open a potent new front to attack the Prime Minister. There is a genuine and profound question regarding the government’s priorities in an increasingly dangerous world. All politics is local, so the saying goes. But after the tumultuous events of the last seven days, could 2026 be the exception that dramatically proves the rule?