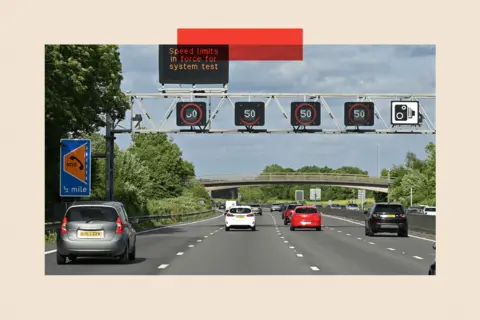

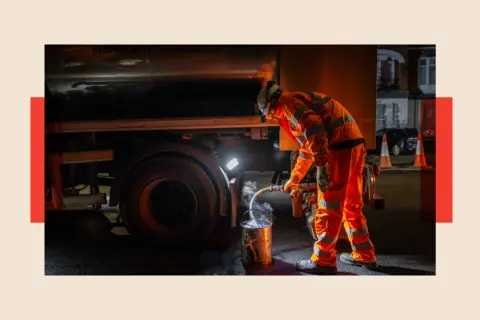

The ubiquitous orange flashing lights and endless stretches of traffic cones have become an all-too-familiar sight on Britain’s roads, a harbinger of delays and mounting frustration for millions of motorists. A recent late-night drive along the M6 towards the West Midlands, encountering two closed lanes and a reduced 50mph speed limit on an otherwise deserted motorway, perfectly encapsulated this common sentiment. For many, including this political correspondent who clocks thousands of miles weekly for a Radio 4 programme, roadworks are a constant, often exasperating, feature of modern travel.

HGV driver Brett Baines, with nearly three decades on the road, echoes this widespread sentiment, noting a marked increase in roadworks that "seem to drag on for months, years." His observation is more than anecdotal; National Highways, the body responsible for England’s motorways and major routes, confirms that the nation is poised to experience even greater levels of disruption. The primary reason for this impending surge is simple yet critical: the vast majority of the UK’s strategic road network, including its roads and bridges, was constructed in the booming car-ownership era of the 1960s and 1970s. These vital arteries are now, according to Nicola Bell, executive director at National Highways, reaching the end of their "serviceable life" and are in dire need of comprehensive upgrades and repairs.

While the focus on increased disruption is particularly strong in England, Wales faces similar challenges, with a significant portion of its highways infrastructure also dating back to the 1960s and 1970s. The Welsh government anticipates "essential maintenance work," though the scale of future increases in disruption remains less clear compared to England, and even less so for Scotland and Northern Ireland. Regardless of the regional nuances, the overarching narrative is one of an aging infrastructure crying out for attention.

The problems caused by roadworks extend far beyond mere inconvenience. Roads are the arteries of the economy, used by almost everyone for daily commutes, deliveries, and leisure. They also serve as a tangible daily interaction with public services, shaping public opinion on the effectiveness of government and infrastructure management. The economic cost of this disruption is staggering. Between 2022 and 2023, England alone saw 2.2 million street and road works, which the Department for Transport (DfT) estimates cost the economy approximately £4 billion through travel disruption. This figure underscores a delicate balance: the undeniable long-term benefits of improved, safer, and more efficient infrastructure versus the immediate, often painful, costs of disruption. The critical question, then, is whether the country is striking this balance effectively.

Beyond the major motorways, local roads are also experiencing a deluge of activity, largely driven by "street works" undertaken by utility companies. In the Hampshire village of Clanfield, resident David voices a common frustration. He points to a notoriously slow four-way temporary traffic light system, the result of extensive utility works to replace old infrastructure. "It’s had a huge impact," he laments, particularly highlighting the lack of effective coordination. SGN, the gas network provider for southern England, defends its ongoing 10-mile pipe replacement project in Clanfield as a "particularly challenging" but "vital improvement" due for completion in May. They assert that they have maintained regular communication with the community. However, for many like David, the explanation does little to alleviate the daily grind. The Local Government Association (LGA), representing councils in England and Wales, confirms this trend, citing a 30% increase in utility company works over the past decade, exacerbating congestion in countless towns and villages.

Funding and governance present significant hurdles. Local councils in England bear responsibility for all highways except the strategic road network. Nick Adams-King, leader of Hampshire’s Conservative-run county council, estimates that fully repairing the roads in his area would cost an astronomical £600 million, while their annual budget stands at a mere £70 million. Although the government has pledged increased funding for local road repairs, promising over £2 billion annually by 2030 (up from £1.6 billion in 2026-27), the gap between need and provision remains substantial. Adams-King also highlights a critical issue of control, noting the considerable leeway utility companies possess in influencing the timing and execution of their works.

A particular point of contention revolves around "immediate permits" for urgent or emergency works, which do not require prior notification to local authorities. These permits accounted for nearly a third of all street works in England in 2023-24, leading some councils to suspect misuse. One authority even reported a "crackly phone line" as the justification for an immediate permit, despite the issue having been known for weeks. The House of Commons Transport Select Committee, in a July report, acknowledged the necessity of these permits but urged the government to review the definition of urgent works. To deter misuse, the government has doubled fines for street work offences from £120 to £240. However, Clive Bairsto, chief executive of Streetworks UK, which represents utility companies, disputes claims of widespread abuse, stating that the Department for Transport found "absolutely no evidence to support that." He maintains that 69% of all utility work is, in fact, planned and coordinated.

The economic ripple effect of roadworks is felt acutely by businesses across the country. In Rochdale, Greater Manchester, Angela Collinge, owner of Amber Pets for 27 years, describes a continuous cycle of roadworks impacting her trade. "As soon as one lot’s finished, another lot starts," she says, leading to "hideous congestion every morning." This forces customers to avoid the area, resulting in a noticeable decline in regular clientele. Utility companies in Rochdale acknowledge undertaking essential upgrades to gas, water, and broadband infrastructure, asserting coordination with the local council and efforts to keep residents informed. Some firms are even trialling simultaneous gas and water works to minimise disruption, a model that could be expanded if successful. However, local MP Paul Waugh criticises a long-term "make do and mend" approach, arguing that utility companies "need to realise the damaging economic impact" and advocating for a more coordinated system.

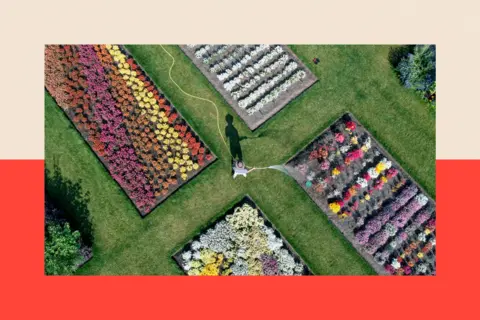

Perhaps one of the most high-profile cases of business impact is the Royal Horticultural Society’s (RHS) flagship Wisley Garden, situated near junction 10 of the M25 in Surrey. National Highways has invested over £300 million in a project to alleviate congestion and enhance safety at this notoriously busy interchange. Yet, RHS Director General Clare Matterson states that the charity has incurred losses nearing £14 million. "We’ve dropped over 350,000 visitors in a year," she explains, attributing this to families and elderly visitors becoming stressed by the difficult driving conditions. Many have cancelled memberships or postponed visits until the works are complete. While the RHS supports the need for improvements, Matterson questions the project’s prolonged duration and significant disruption, especially given an additional nine-month delay attributed by National Highways to "extreme weather." RHS Wisley is now seeking compensation. In response, National Highways has adopted an "unprecedented" strategy of full M25 weekend closures to accelerate the works. Nicola Bell explains this "short sharp shock" approach: "Actually, you [are] going to get more done by closing it for five weekends throughout the duration of the works than prolonging that disruption by perhaps just closing one lane." She expresses sympathy for businesses like RHS Wisley, acknowledging the challenge of major infrastructure projects adjacent to commercial operations.

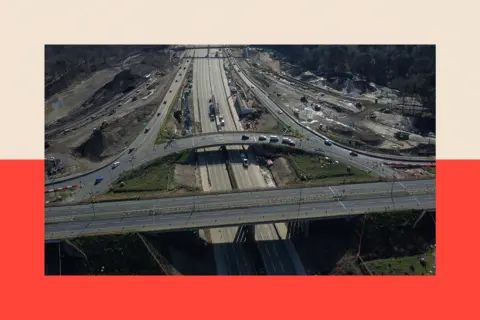

On the strategic road network, motorways and major trunk roads, though comprising just 2% of England’s roads by mileage, carry a third of all traffic and two-thirds of all freight. Data from the DfT indicates that delays on these major roads increased between 2019 and 2025, partly due to roadworks. The government, recognising the "costly delays" to businesses and the "frustration" for road users, has made addressing these delays a priority for economic growth, announcing a £25 billion spending plan for the strategic road network between 2026 and 2031. The "short sharp shock" approach is also being piloted elsewhere. In Hampshire, for instance, a concrete tunnel for a new garden village of 6,000 homes was constructed off-site and then slid into place beneath the M27 over Christmas, requiring a full motorway closure. John Beresford, managing director of Buckland Development, explains this was designed to minimise long-term disruption. James Barwise, policy lead at the Road Haulage Association, supports this, noting that pre-telegraphed, short-term full closures are often preferred by hauliers over months of lane restrictions, despite initial local disruption.

Local authorities are exploring additional solutions, such as "lane rental schemes," which charge utility companies up to £2,500 per day for works on busy routes during peak times. Councillor Tom Hunt, chair of the LGA’s inclusive growth committee, believes this financial incentive encourages more efficient and faster work. Currently, only a few councils have these powers, but the Transport Select Committee advocates for wider rollout across England, with ministers indicating that mayors will gain the authority to introduce such schemes in their regions. However, Clive Bairsto of Streetworks UK counters that lane rental costs are ultimately "passed directly on to the consumer."

Ultimately, three recurring themes dominate discussions around roadworks: coordination, communication, and duration. While various solutions are proposed, clear and immediate answers remain elusive. Nicola Bell of National Highways aptly summarises the situation: "Across all of our infrastructure, whether that’s energy, water – you could argue they have all seen a lack of investment, which is why you’re now seeing increased levels of road works as we now invest." With a government committed to infrastructure as a driver of economic growth, roadworks are undoubtedly here to stay. The enduring challenge will be to manage them with greater effectiveness, mitigating their impact on daily journeys, businesses, and the collective patience of the nation’s motorists.