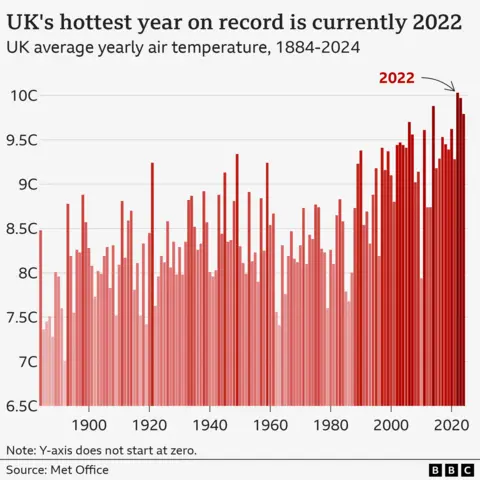

Rising temperatures in the UK are poised to become "the new normal," a leading government climate adviser has warned, calling for urgent and extensive preparations to mitigate the escalating impacts of climate change. This stark warning comes as the Met Office, the UK’s national weather service, revealed that 2025 is on track to surpass all previous records, making it the UK’s hottest year since systematic observations began in the late 1800s. The relentless warming trend, unequivocally linked to human-caused climate change, continues to push temperatures to unprecedented highs.

With merely a week remaining in the year, the average UK air temperature across 2025 is projected to settle at approximately 10.05C. This figure would narrowly exceed the current record of 10.03C, which was set just three years prior in 2022. "This is our future, encapsulated in data," stated Professor Rachel Kyte, the UK’s special representative for climate, in an interview with the BBC. Her message was clear and urgent: "Now the question is ‘how are we going to prepare ourselves and build our resilience to this?’"

The methodology behind the Met Office’s projection is robust, incorporating observed temperatures up to December 21st and making a conservative assumption that the remaining days of the year will see conditions approximately 2C below the long-term December average, with slightly cooler weather expected over the Christmas period. While absolute certainty is always elusive in such predictions, the data strongly indicates that 2025 is the most probable outcome for a new record. This would mark the sixth instance this century that the UK has registered a new annual temperature record, following 2002, 2003, 2006, 2014, and 2022, underscoring a clear and accelerating pattern of warming.

The year 2025 has been characterized by persistent warmth and a notable lack of rainfall, rendering the country particularly vulnerable to widespread droughts and devastating wildfires throughout the spring and summer months. While natural variability always plays a role in yearly temperature fluctuations, the scientific community is unequivocal that the overarching trend of rapid warming is directly attributable to anthropogenic, or human-caused, climate change. "The pollution [carbon dioxide] we’ve put in for the last 20-30 years is now what is driving this warmth, and so not curbing emissions well enough means we’re going to continue to see these kinds of impacts," Professor Kyte emphasized.

She underscored the critical need for the UK to develop comprehensive "resilience" to the inevitable reality of higher temperatures. This requires significant and sustained investment in both nature-based solutions and robust infrastructure. Investing in natural systems, such as extensive tree planting, restoring peatlands, and implementing sustainable land management practices, can help regulate local temperatures, improve water retention, and enhance biodiversity. Simultaneously, infrastructure adaptations are crucial, including the development of more efficient cooling systems for buildings, upgrading water supply and drainage networks to cope with extreme weather, and designing urban spaces to mitigate the urban heat island effect. "If we don’t invest in our adaptation now, it’s going to cost us way more in the long run," she warned, highlighting the economic imperative of proactive measures.

By the close of 2025, a sobering milestone will be reached: all 10 of the UK’s warmest years on record will have occurred within the last two decades. This dramatic concentration of high temperatures provides compelling evidence of a rapid and sustained shift in the UK’s climate. "Anthropogenic climate change is causing the warming in the UK as it’s causing the warming across the world," affirmed Amy Doherty, a climate scientist at the Met Office. She further elaborated, "What we have seen in the past 40 years, and what we’re going to continue to see, is more records broken, more extremely hot years… so what was normal 10 years ago, 20 years ago, will become [relatively] cool in the future." This illustrates a fundamental redefinition of what constitutes "normal" weather in the UK. Mike Kendon, another climate scientist at the Met Office, described the observed changes as "unprecedented in observational records back to the 19th Century," pointing to the profound nature of the current climatic alterations.

The foundation for 2025’s expected new record was laid by persistent and unusually high temperatures throughout the spring and summer. Although the long, hot, sunny days may now seem a distant memory as the festive season approaches, both spring and summer were officially the UK’s warmest ever recorded. Each month from March through August consistently registered more than 2C above the long-term average for the period between 1961 and 1990. While temperatures peaked at 35.8C – a figure below the historic highs of over 40C witnessed in July 2022 – the defining characteristic of 2025 was the recurrence of hot spells. Four separate, albeit relatively short-lived, heatwaves were officially declared across large swathes of the country.

These repeated periods of intense heat prompted the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) to issue multiple heat-health alerts throughout the summer. These alerts are crucial for public safety, signaling to healthcare providers and the public the increased risks, particularly for vulnerable populations such as the elderly, young children, and individuals with pre-existing health conditions. Prolonged exposure to high temperatures can lead to serious health consequences, including heatstroke, dehydration, and exacerbation of cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses. Beyond health, the sustained heat also impacts daily life, from disruptions to public transport and essential services to reduced productivity in various sectors.

The warm conditions of spring and summer were exacerbated by exceptionally low rainfall. Spring 2025, in particular, was the UK’s sixth driest since 1836. This severe lack of precipitation, combined with the drying effect of elevated temperatures, pushed large parts of the country to the brink of, or into, official drought status. Through the summer, the Environment Agency in England and Natural Resources Wales formally declared droughts across several regions. Similarly, parts of eastern Scotland experienced "significant water scarcity," as reported by the Scottish Environment Protection Agency.

These declarations triggered a range of measures, including hosepipe bans and restrictions on non-essential water use, highlighting the strain on water resources. The agricultural sector bore a heavy burden, with concerns over crop failures, reduced yields, and stress on livestock. Ecosystems also suffered, with reduced river flows threatening fish populations and wetland habitats.

Recent rainfall has provided some relief, easing the drought situation across many areas, and most regions are no longer under official drought status. However, water levels in aquifers and reservoirs remain below average in some places, indicating a significant deficit that still needs to be replenished. Jess Neumann, an associate professor of hydrology at the University of Reading, articulated the gravity of the situation: "There’s a huge deficit to be made up, and there’s a huge implication, not just for people who are farming the land [and] growing food, but our rivers, our aquifers, our availability of drinking water." She further noted that the increasing frequency of swings between prolonged drought and intense flooding events makes it exceedingly difficult for communities to adapt and build resilience to these escalating weather extremes.

The prolonged dry, warm weather also created ideal conditions for wildfires, leading to an unprecedented year for blazes across the UK. By late April, the area of the UK scorched by wildfires had already reached a new annual record, according to data from the Global Wildfires Information System, which dates back to 2012. Throughout 2025, more than 47,100 hectares (471 sq km or 182 sq miles) have been burned, dramatically surpassing the previous high of 28,100 hectares recorded in 2019.

Andy Cole, chief fire officer at Dorset & Wiltshire Fire and Rescue Service, reported that firefighters in his region had responded to over 1,000 wildfires this year, describing the number as "unprecedented." He told the Today programme, "I’ve been doing this for over 20 years and we’ve seen a marked increase in the number of fires we’re having to deal with in the open." These wildfires not only pose immediate threats to lives and property but also cause extensive ecological damage, release significant carbon emissions, and place immense strain on emergency services. Moorlands and heathlands, particularly in regions like the Peak District and the Scottish Highlands, are increasingly vulnerable.

As the UK continues to warm, driven by humanity’s relentless greenhouse gas emissions, scientists anticipate an increase in the frequency and intensity of weather extremes. "The conditions that people are going to experience are going to continue to change as they have in the last few years [with] more wildfires, more droughts, more heatwaves," Dr. Doherty explained. She also highlighted another critical aspect of future climate change: "But also it’s going to get wetter in the winter half-year, so from October to March… the rain that does fall will fall more intensely, and in heavier rain showers, causing that kind of flooding that we’ve been seeing this year as well." This dual challenge of hotter, drier summers and wetter, more intense winters presents complex adaptation challenges for infrastructure, agriculture, and public safety.

The UK’s experience of extreme heat this year is not an isolated incident; it aligns with a broader global pattern. The world as a whole is currently on course for its second or third warmest year ever recorded, according to the European Copernicus climate service. This global context underscores the systemic nature of climate change, with heatwaves, droughts, and extreme weather events impacting regions from Europe and North America to Asia and Africa. However, the international consensus on tackling climate change is simultaneously facing significant tests. Some leading producers of fossil fuels, including the US, have shown signs of backtracking on their net-zero commitments or slowing the pace of climate action. Such reversals threaten to undermine collective global efforts, making it harder for all nations, including the UK, to meet ambitious emissions reduction targets and avert the most catastrophic consequences of a rapidly warming planet.

Additional reporting by Justin Rowlatt, Kate Stephens and Zahra Fatima